GOLD-SEEKING ADVENTURE.

The Career of Mr. J. B. Nichols Twice Marked by Extremely Narrow Escapes From Death. – Faced Starvation and other Hardships in Seeking the Yellow Metal.

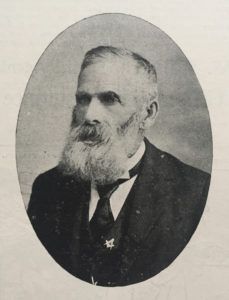

It gives us much pleasure to this week place before our readers the portrait of Mr. Jazaniah B. Nichols, a native and for many years resident of Danby, but now located at Asbury Park, N. J.

The subject of this sketch was born December 22, 1828, and was the eighth of the ten children of Isaac and Abigail (Barrett) Nichols. Of this large family one died in infancy and was buried with the mother, one sister died at the age of twenty-nine, while the remaining eight all passed their seventieth birthday; and four are still living, whose ages range from seventy to eighty-nine years. The father died at the age of eighty-six, but the mother died at the early age of forty-three.

Mr. Nichols was educated in the common schools, with the addition of three months in the North Granville Academy, and commenced working on the farm as soon as he was old enough to handle boys’ tools. When a small boy, of perhaps five or six years, he met with an accident by which he nearly lost his life. The hired man was grinding a scythe on a grindstone operated by water power, and J. B. being greatly interested in the operation, got so near that the crank caught in the pocket of his small trousers. In these days no harm would have ensued further than a torn garment, but the homemade linen cloth in which the little man was clad was so strong that he was lifted from the ground and whirled around and around with great rapidity, and striking with such force as to fracture his hip so badly that he was crippled for many months, and the effect of the accident is seen today in a peculiar manner of walking. It was a pretty serious affair in a family of young children from whom the mother had recently been removed by death, placing a heavy responsibility on the shoulders of the eldest sister, who was early called to be mother as well as sister to them all; but her love and care and tender sympathy has never failed—and now, in her serene and peaceful old age, she reaps the reward so faithfully earned.

Upon attaining his majority Mr. Nichols taught school in Dorset, and afterwards worked for Moulton Fish at $12 a month. Then, after teaching one term in the home district, he traveled to Bellevue, Ohio, where his eldest brother then resided, and it was there that he caught the fever which carried him, through many perils and adventures, to the gold fields of California.

Mr. Nichols says that to write an obituary—and a premature one at that —is rather a solemn thing to do. However, he has consented to give a few incidents of his California experience, hoping they may prove, if not instructive, in a measure entertaining to our many readers—and we will permit him to tell his story in his own language:

“As my friend, H. P. Griffith, has given a few incidents of his experience as a forty-niner (we old goldseekers all date from ’49), I will place before your readers a few of my own.

“While engaged in teaching school in Ohio an outbreak of gold fever occurred in that section, and your humble servant was infected with the contagion. The boys were to start in four days, which made it necessary for me to hustle to find a substitute in the school, procure funds, clothing and all necessaries for a long journey—but J. B. got there, and started with the party.

“In the meantime, my father (through the agency of some bird or by other means) ‘caught on to’ the scheme and offered me a thousand dollars if I would give up the idea of going—for California was further from home then than it is at this time. But money does not always win. We started from Bellevue, Ohio, in two four-horse sleigh loads and were carried to Painsville, where we took the train and arrived in New York in due time.

“Unfortunately, we found all steamship tickets sold in advance for several months. As the saying goes, that was a ‘setter.’ We could not well stay in New York all that time; we couldn’t go forward, and we wouldn’t go back. Yes, indeed, it was a ‘setter;’ but some enterprising capitalist invented an independent line—which, by the way, proved to be extremely independent, for on arriving at the isthmus we found they had not as much as a fishing smack on the Pacific side. We mistrusted as much while in New York, and had seen that sufficient funds were taken on our steamer to refund to us our fare on the Pacific side. Small steamers took us up Chagres river as far as navigation permitted; then we took to small boats propelled by poles in the hands of negroes, and finally we were compelled to take ‘shanks’ horse’ for the remainder of the way from a place called Gorgona, twenty-eight miles from Panama.

“Panama was a curious old town, the buildings built of adobe and brick, with tile roofs and wooden shutters, there being not a pane of glass in the city, which is enclosed by a wall of solid masonry, with heavy barred gates, which were regularly opened and closed morning and evening. The city walls and many of the buildings were shattered and broken, giving silent evidence that General Bolivar was not a myth. His cannon were placed silently at night on circular mountain—something in the form of our old Dorset—from which place he so effectually bombarded the city as to cause its hasty surrender.

“I must relate what occurred during our stay in Panama. On board the steamer from New York was a man, about fifty years old, who had a shovel and never seemed to be without it. I saw him again while crossing the isthmus—the man and his shovel—and also in Panama. Well, I saw him once more, but he was dead—stabbed through the heart—and, behold, the shovel was still by his side.

“Several thousand people en route for the gold diggings, as well as ourselves, were detained for want of transportation. Great indignation prevailed. Agents of the great independent steamship transportation line suddenly disappeared, threats of prosecution were on tap and much confusion prevailed. Many returned to their homes, while others obtained transportation on sailing vessels. Such as had the means could get passage on regular liners on payment of one thousand dollars.

“Of my party, three returned to their homes, the balance got passage to ‘Frisco as best they could. Several of us got away on bark Emily (1,000 tonnage) at a cost $250 each. Now, the bark Emily was not clipper built, by any means, but was nearly as round as a tub—consequently, traveled at much the speed of oxen in a plow field. The Emily was provisioned for sixty days. Can you imagine what a funny time we had when to tell you the time from starting from Panama until our arrival in ‘Frisco was one hundred and eighty days? If space permitted, I would be glad to tell many details of this ‘unhasty’ voyage, but will merely say that while starvation prevailed, our suffering was more for water than food.

“We (the passengers), took charge of dispensing food and water. The captain and officers of the ship as well as the passengers were put on allowance rations. The captain, an Englishman whose name was Wilson, offered the passengers, measure for measure brandy from his locker (which I had been more than once around the world ) for water—with no takers. A pint of water per day was each man’s allowance with which to allay thirst and cook our beans and rice—they being the only eatables on board except salt pork. Of course we drank but little and ate less.

“Out of two hundred and seventy-live passengers, thirty-eight were sewed up in blankets, weighted with coal at their feet and tipped from the ship’s rail into old Pacific’s briny depths. Sorrow is in my heart as I recall their sad fate, for suffering together and the intimacy of the long voyage brought close friendship. It was pitiful indeed to hear their insane, feverish cries for water.

Much has been written of burial at sea, but only a witness can ‘realize the solemn sadness of such scenes. That these young, enterprising men, so eager and earnest to advance their prosperity, so far from father, mother, friends and home, should meet such an untimely fate—ah! these are sad memories; let them pass.”

Mr. Nichols returned from California in the summer of 1858. The winter after he married Sarah, daughter of David and Jemima Boyee, and began housekeeping in part of the house then owned by Mrs. George E. Kelley (now Mrs. E. O. Whipple). He entered into partnership with C. M. Bruce, in the general merchandise line, but sold out his interest and carried on the tin business for several years, hiring a number of peddlers. Later, he bought the house now owned by Mrs. D. H. Lane, and where he lived five years, selling groceries and general merchandise in the old marble store.

In 1868, Mr. Nichols bought a farm in Manchester, where he lived eighteen years and where he still owns real estate. He exchanged his farm for Iowa property, which he rented for several years and finally sold. In 1886 he again visited California, making, however, but a flying trip—very different from the tedious journey of ’52.

Eight years ago Mr. Nichols became interested in Monmouth County, N. J., property, where his brother, Anthony, had resided many years previous to his death. Here he has invested considerable money in renting property just outside the city limits of Asbury Park, a lively, growing coast resort. Mr. and Mrs. Nichols’ only remaining child married Lucy, daughter of Barney and Julia Decker of Danby and they, and their two children are also living in historic old Monmouth County, on a farm about four miles from the sea.

Mr. Nichols became a member of the noted “Boys’ Club,” at the Lake Griffith outing last June, and it is to be hoped he and all who were present on that occasion will be able to meet again with their most hospitable host, Mr. S. L. Griffith, at his delightful mountain retreat in 1903, soon after nature has put on her fresh robes of green again.